One of the prevalent myths about the evil wrought upon today’s young generation by “screen time” is that computers discourage their users from social interactions. The claim is that when people use computers, they cut themselves off from direct personal interaction with their fellow humans, and become instead solitary islands separated from the world around them. This position is usually maintained by adults who, themselves not really at home in the Information Age, have engraved in their minds images of a child sitting alone – in front of a monitor, or hunched over a smartphone or notepad, or focused on the display on a laptop – with no others around, hour after hour, “addicted” (as they often call it) to this “self-destructive habit”.

The whole idea brings to mind a series of scenarios that must have played out several times in human history. Consider the first appearance of documents written on parchment or papyrus, on which the beautiful, melodic accounts of story-tellers relating the history of their nation, or the profound oral lectures analyzing the philosophical foundations of thought, were finally recorded in a form that could be circulated widely to an audience that never had the opportunity to hear the original telling. What an upheaval that new means of communication must have caused in the lives of communities fortunate enough to enjoy them! I can just imagine a group of adults in Athens bemoaning the sight of the flower of Greek youth hunched over the latest edition of Plato’s dialogues, one or two individuals at a time at most, each at his own table or in his own home; “those kids are addicted to those newfangled bookrolls. They don’t talk to each other, they are becoming asocial.”

Never mind the fact that writing enabled people far removed from each other geographically, with no hope of ever communicating face-to-face, to exchange ideas, plumb the depth of each others’ thinking, and even form societies in widely diverse geographical locations – social organizations, to be precise – devoted to discussing and studying the content found in books, developing new approaches to that content, debating and refining them, and then, through the same written medium, exchanging their new approaches with others, once again far removed from any possibility of direct contact. Asocial? Really?

Anyone spending time at Sudbury Valley sees the same kind of outcome from students’ (and adults’) use of the latest newfangled media, conveniently grouped under the general category of “screens”, linked to screens of hundreds of millions of other people throughout the globe. And not only linked to them, but linked to them virtually instantaneously, allowing for dynamic and immediate access to information, and to each other. Sometimes an individual at school will be doing this individually and alone;

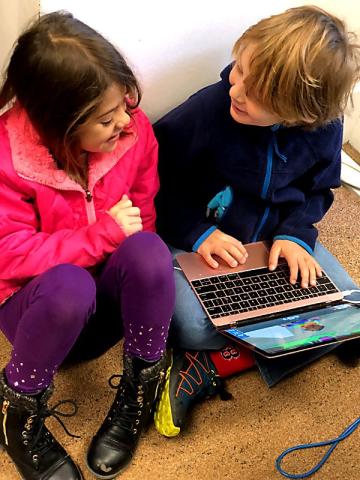

sometimes a number of students sitting on a couch in close physical contact with each other will each be doing this together, but each individually; and sometimes a number of students will be doing this in a group, all huddled over one screen, sharing the experience – with emphasis on the word “sharing”, to laughter and exclamation and wonder, all essential features of direct social interaction.

Sometimes a myth is a verbal representation of an underlying reality; other times, a myth is just a pure imaginary construction that flies in the face of experiential reality. The notion that “screen time” is an isolating pastime is the latter kind of myth, the kind that flies in the face of experiential reality.