“Mobility was a big part of what was different about the school from any other institution. Mobility and randomness together let you find the things you're interested in. You're not stuck anywhere . . . the whole day you're doing stuff you're excited about.”

My parents started the brainwash pretty early. They started telling me what a horrible place my local public school was, and how the kids had to sit for six or eight hours in a chair and they weren't even allowed to move or go to the bathroom without permission. To a hyperactive five year old, all this stuff sounds like a description of Hell – like the ninth circle of Hell, to be precise. I remember very distinctly getting a letter when I was six years old from the public school, saying, “We’re delighted to have you as our latest inmate.” I was totally triumphant because I knew that SVS was going to be opening. So, even though I had never been to either school, I knew already from the brainwash that I had just gotten a ticket out of Folsom State Prison.

My understanding was that my sister and I were going to be in a place where we wouldn’t be told anything, and we could just run around and do what we wanted. That was what I had been doing all my life up to that point anyway. My life as a kid, which was running around and doing what I wanted, was going to continue at SVS, instead of going to a school where I would be sitting down and learning things in a set order, with my time all divided up.

To me the whole idea of sitting down was just anathema. I was not into sitting down! I was a runaround kid. I was outside through most of my early school career, even in the winter, and I couldn’t understand how the whole idea of being penned up related to being a kid at all. The whole point of being a kid was to run around. When you’re a little kid, adults seem really tired and slow and there’s this big feeling that that’s going to happen to you one day, so you had better play and have fun while you have all this energy.

One of the things that made the school much “cooler” than home, aside from having a lot of other kids and friends, were the physical things you could do. For instance, there was a bunch of large boulders that we called “The Rocks” just north of the parking lot, and we would jump between them and play all kinds of games; sometimes the boulders were our space ship and things like that.

I remember when all the elms lined the driveway coming down to the school. Later when they had to be cut down, we saved the big stumps and put them in a stairway formation. We used to play on those constantly, until they rotted down to nothing. We also played on the trees themselves when they were first cut down. There was an amazing huge cement thing in the middle of one tree; the tree had been diseased a long time before and someone had filled it with cement. We were all quite mystified.

We had a game in which you had to go around as much of the school building as you could on the building itself, on a little ledge of granite. There were certain things in that game that only the big kids could do, such as the hand over hand maneuvers, and you had to grow into them, and there were some tricky areas. As a little kid you would do as much as you could and, as you got stronger and older, you would do more and more until you could finally go around the whole building without touching the ground. Of course, we thought no adult knew we were doing it. A lot of the stuff we did was a little dangerous; like most of the things we did, this was both a physical challenge and a mental challenge.

The big kids played soccer. Mitch would say, “You little kids should play soccer, too.” Now, we’re six and they’re sixteen, seventeen, eighteen and we would get picked as a group. There would be a wad of us, and Mitch would tell us to just basically cluster together, and attack anybody who had the ball who was on the opposing team. It was totally fun and it was a completely unconventional approach. We were running in a frenzied pack after some big kid who had the ball. And, of course, there would always be this great moment where someone would kick the ball hard, trying to take a shot, and it would cream one of us little kids right in the face. Someone would say, “Time out, time out, everyone!”, and all the big kids would cluster around us for about a minute. And then we would get up proudly, because you can’t really get hurt by a soccer ball hitting you in the face. It would just stun you for a second and the game would continue and we would feel so tough for doing that.

Later, when I was a big kid playing with little kids in the same way, I realized how incredibly hard it is, because you’d be wanting to take a shot, but there’d be some little kid you were trying to avoid launching the ball into. And, of course, eventually you would launch a ball and it would smack some little kid right in the face. “Time out”, and you’d all run to the little kid and see that you hadn’t killed him. And then you’d breathe this total collective sigh of relief when the little kid got up. And then you’d remember: this happened to me twice a day when I was little and there’s nothing really harmful about it.

We used the woods a lot, especially during the winter because the best sledding trails were out there. The idea of a six year old just wandering off into the woods with another six year old and a sled to go do some trail seems kind of mind-blowing to me now, but at the time it just was the most natural thing in the world. You didn’t have to tell anyone you were leaving school, and there were always groups of kids going there, so there were probably some older kids, maybe teenagers, who knew the way. It’s very hard to remember precisely because my “peer” group stretched way out to the older ages, and you would always see people in the woods.

The school was full of great hiding places. We played hide and seek, or a variation of that, a lot. Then there was the barn. You felt physically kind of far away from the school because nothing you’d do could be heard, so it was a wonderful secret world. There were no adults because the staff mostly stayed down in the school. We would play war, using the underground part of the barn, the main floor of the barn, and the attic. It was the ultimate place to play war because you had all those levels to hide in. It was a very private world up there. Eventually, the attic of the barn became off-limits because it was considered unsafe. From our point of view, that was hilarious, because we were so used to jumping out the barn attic window and crawling onto the roof, that the idea of the attic having only one exit and therefore being dangerous was kind of ridiculous to us. Our whole trip up there was finding as many exits as possible!

The maze swamp, which no longer exists, was a really fun place where we would try, often unsuccessfully, not to get into the swamp. We would be on the branches and stuff. It was also “the” place to play with a microscope. You could spend all day with a microscope just looking at the creatures that you’d scooped in one cup of water, because there were every manner of creature. You would see a creature swimming around in the water and you’d pipette it out and block it on the slide and look at it in the microscope and you would see everything: mosquito larvae and all these weird other creatures we couldn’t even name. Something I remember establishing really quickly — which was a little unintentional ecology lesson, I suppose — was that there were many more creatures in the swamp than were in the pond.

We were ring-led in a lot of stuff by Ken; he was five years older than us and very, very inventive. He’d suddenly come up and say, “Hey, did you know that there’s a room back here?” It might be down behind the boiler room in some chamber of the basement of the school that no one had ever bothered to go into. Suddenly that would become everyone’s hideout. We’d all be down there and then one day the staff would suddenly discover that we were building fireworks or something down there under Ken’s guidance and people would say, “Oh my God, you can’t go in this room. You’re building fireworks ten feet away from the boiler”, or something like that.

Another couple of kids and I used to hang out in the smoking room a lot. I was six or seven. I was really interested in the kids who smoked and talked about rock and roll and drugs. We would sit in the beautiful teenage girls’ laps and listen to them talk. They would kind of mother us. No one was worried that they were going to be corrupting us or that little six year old ears were hearing it, which was paying us a lot of respect — assuming we could handle all this information and not flip out. They tended to let you hang out with them regardless of what they were doing. Having a six year old asking you questions all the time might not be what you want when you’re a fifteen year old kid trying to do something, but they were very inclusive. As little kids, we thought that was the way to be.

Hearing these kids describe their experiences was amazing. These were kids who had the guts to go to a school and just hang out and talk and not even pretend to do anything academic. Their conversations were incredibly interesting, because they were on the cutting edge culturally. We knew their music backwards and forwards. The most important music of my life is still the music of ‘67 through ‘70, the music that my heroes were excited about. I still constantly go back to it, and feel the most intense emotions about it.

The antics of Neal are very intense early memories for me. He really took us little kids into his world. We were his audience. I remember there was a piano that had all thumbtacks stuck in the old hammers, and he and Darryl would play honkey-tonk piano. It sounded really beautiful. Neal would play “Why Don’t We Do It in the Road?” and he would sing at the top of his lungs. He was constantly doing exciting creative things, drawing or making up music or singing. He also used to say, “Do you want me to take you to Birdland?” We would always say, “Yes,” and he would hold us up over his head and run around like a maniac through the school or around the outside and we would be objects flying over his head. Some of the other big kids used to play “rumble” with all us little kids. We would clime on a big kid and get him down on the ground and then he would get up, and we’d all fall off him and then try to pin him down again.

We had a lot of water fights in the old days of the school; we did crazy things like putting cups of water on doorways or throwing wet paper towels — we called them gloppies — at each other. One time Cameron and I poked holes in all the Dixie cups in one dispenser, so that when people came to drink it would dribble all over their shirts. Ken once brought in a syringe that was used for giving a cow a shot. You could fill it with two cups of water and shoot a pinpoint line of water 30 feet with deadly accuracy by pushing the syringe fast. We would walk around the school in a group together clustered around each other and someone would have the syringe in the middle of the group. You could fire it right between two people and hit a person from across the room. They wouldn’t know what happened. Later on you’d get caught and someone would say you shouldn’t bring a syringe to school and we would argue: there’s rules against squirt guns, not syringes; this is agricultural.

The cleverest prank I think Ken ever pulled was wiring a pump in the basement, leading it up through the kitchen and leading the wires through a door jamb so that he could stand in the kitchen doorway, talking to his chums so it looked like they were just involved in conversation, and every time he wanted to he would put the two wires together and the pump would start and a jet of water would come out of a little concealed area in the floor and douse someone. This went on for hours. No one knew where it was coming from. Everyone was running around trying to figure it out. Finally Ron saw there was this trail of drops leading to the thing and he got down on the floor and he crawled right to it and looked right at it, and Ken gave him a big blast right in the face and then told everyone how he had done it.

Ken built a running car completely out of scraps that he found in the junkyard. It had a Studebaker radiator, a working engine, the accelerator was a string you pulled, and it had a steering wheel and a back to it that was like a pickup truck. He totally built it in the basement of the school. He wasn’t old enough to drive, so the rule was that he could drive it on the school property. He would zoom us around in the back of his truck and we would have tremendous fun.

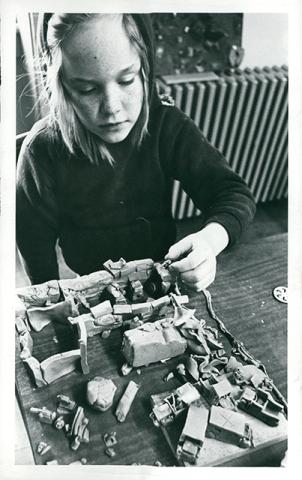

And then there was Plasticene Island. The scale was about six feet to an inch. They used plasticene modelling clay that you don’t have to fire. It doesn’t dry and you can keep remolding it. There was a big table in the art room that somehow became “Plasticene Island.” Different kids sat in different positions and they had “land.” It was kind of a combination of the Old West and the twentieth century. Everyone staked out little homesteads. Ken set a standard. He was a mechanic. He had built the truck. On Plasticene Island, if you wanted to have a car, the car had to have an engine, a carburetor, sparkplugs, a fan and a fanbelt. There was a whole checklist of things you had to have that made your engine realistic enough. Ken actually manufactured cars for other people in a factory called The Plotzmobile Factory.

He had little templates that he had drawn out and he made little Plotzmobiles and sold them to kids for the money that was also made on Plasticene Island, in the mint. Darryl was in charge of printing the Plasticene Island money. There might have been some clever little thing where you could buy a certain amount of Plasticene Island money for a real quarter because if I know Ken, he managed to make a real buck out of this somewhere! He would sell the Plotzmobiles and his brother, Dylan, had the DW Sprint, which was a much sportier car than the Plotzmobile. The Plotzmobile was the workhorse.

But then Ken would get bored and you’d suddenly see him rolling out about a thousand men and you’d say, “What’s going on?” And suddenly all the men would have little rifles, and he would attack all his neighbors and totally overwhelm them. For big things like wars you had to get the people who had land together. When there was a war going on, which was frequently, I would go to each side and hear what their plans and strategies were, because I wasn’t a participant. The kids who actually did it would spend hours and hours doing it. But Ken’s trick was to go in there when no one was there and make a thousand guys! You’d come in and suddenly you’d realize that the birthrate over at his place had gone out of control. At one point he got bored with the conventional attack strategy and he built a huge factory capable of making large machines. Then he had the factory build an enormous bulldozer and he proceeded to push some of his less favorite people into the sea. He just bulldozed their houses into the sea. He had this philosophy, that I tend to subscribe to too, which is that too much peace makes life kind of boring.

Making money on the Plotzmobile wasn’t enough, so he built an oil refinery on the island, which was totally realistic. He built it right out of a book on oil refineries and we all learned at that point how oil refineries worked. Then he sold gas, because once there was an oil refinery, you couldn’t just run these Plotzmobiles around on air. There was a whole world, totally fascinating, that evolved in miniature. It was such an amazingly complete world, and it was a complete world of art. It was all hand made. Even more amazing was the social world that evolved. It was very much the Wild West meets the Twentieth Century. There was a frontier element, which is very dear to Ken, because he’s kind of a modern frontiersman; however, it was a technical world. It reminded me a little of that old TV show called the Wild, Wild West which was a science fiction western.

Dominic was a kid who became a mortician. As a teenager he was fascinated with autopsies and all kinds of medical things. He would bring in whole heads of cows or pig fetuses or cats — any animals he could get. He would dissect and we would watch and we would dissect little things. When he was cutting open the skull of the cow, which was actually an amazing thing because you could look at the brain and everything, he would give us the eyes and we would dissect the eyes and see the lens and the retina at the back. This was big time, very exciting. I remember the pig fetus and the cows skull specifically because they were so powerful. When there was a dissection going on, the whole school was abuzz, and we would all run there and Dominic would be in his white gown, and Hanna would be showing him where to cut.

Homemade ice cream days were always special celebrations. There was a whole series of specific events that had an annual feeling to them. The ice cream day would happen some nice warm day in Spring. Suddenly ice cream machines would appear and Margaret would be carrying around butter and sugar and cream, her favorite ingredients, and everyone would be making ice cream, and there would be an assembly line of kids scooping it out and making sundaes for other kids. Everyone would have known about it the day before, so they’d all bring their dollar to buy their ice cream, and it would end up funding a new oven for the Cooking Corporation, or whatever.

In the early days of the school there were almost no rules. The basic rules were: don’t disturb anyone, don’t hit anyone, don’t bother what they’re doing, don’t make noise in the reading rooms, and that was about it. I remember being conscious of an abandon, an excitement about living life without cumbersome rules. The basics were like the Ten Commandments, rules that made sense to everybody in every age group. And everything else was a sense of complete freedom and inclusion. You were in on all this stuff. You were not watching it. You were part of it. That was tremendously exciting and, as I got older, I sensed that part of it must have been cultural, and not just inherent in the way the school is set up, because kids definitely change. By the time I was an older teenager, I found myself, in a certain sense, much wilder than the younger kids who had become more conservative. One of the key things about the school being free is that it changes a lot as an institution. The culture changes. School is such a fluid setup that it immediately responds.

In the early days here was also a sense of time to burn. Before anyone knew how to run the school at all, we used to spend wonderfully lengthy amounts of time in School Meetings, or creating the judicial system, because there was no sense of how to get these into an efficient framework. I personally found it very, very exciting. You would have School Meetings that would last from one to five and then begin the next day and last from one to five. And it might go on two or three days out of a five day week.

There was a much different atmosphere as I got older, a lot more of a sense of responsibility. In the old days, no one worried about the students cleaning the school, or anything like that. The staff just did everything. Later on when the staff realized they couldn’t do everything all the time, and that we weren’t a bunch of babies, there was more of a sense of civic duty. There was more of an adult feeling to the school. I’d characterize the earliest years as more of a kid feeling. When I was older, it was more realistic and the kids were expected to understand, at least, or participate, which was probably healthier.

There was also lots of very intense rhetoric and debate about a large number of issues that seemed really critical at the time, like the candy store. A kid had a candy store in an unused closet. We all wanted to be able to buy candy. And then, for some reason, somebody decided that maybe it’s not such a great idea to let one kid get rich by using the school closet as a way to destroy everybody’s teeth. I forget the exact justification of why it was closed down. Maybe it had something to do with the idea that the school wasn’t exactly a free enterprise zone where any enterprising kid could just milk his fellow students for whatever they could get; that the point of the school wasn’t to give a place of business to a twelve year old running a candy store. It was an incredibly large debate, and the upshot of it was that he had to close his candy store.

It wasn’t difficult to find friends; people as a general rule were very nice to each other. I was the same as any kid. I had one or two best friends who I had a love/hate relationship with in that I did everything with them, but they drove me nuts. It’s very much like marriage. You’re with someone who just basically drives you insane; you’re with them all the time.

The games we played went in cycles. Fads would spring up: someone would bring a cribbage board to school and would teach a few kids how to play cribbage. Before you knew it, everybody was playing cribbage. It would get very intense for maybe a month. Then people would just naturally burn out on it and move on to the next thing. It was competitive, I think, in a healthy sense, but it was more that there was an intensity about it. Cribbage was a new and exciting thing that you wanted to completely master. But it would be in the moment. You would just be trying to play your best hand of cribbage.

Every now and then, we’d play for a penny a point or two cents a point, and then someone would get really beaten. You’d start out playing for a penny a point, it would go to two pennies a point, let’s say, it would become four, it would become eight, it would become sixteen. Then you’d get double skunked which made it thirty-two, sixty-four cents a point and you got beaten by a hundred points. And some kid would suddenly end up losing seven bucks at a game of cribbage. I remember one time when Ron and Mitch were playing. When the game was over, they realized that Ron now owed Mitch twenty five bucks for this one game of cribbage. Ron got so mad, he picked up the cribbage board and threw it up at the ceiling of what was then the flowered lounge, and from then on there was a little indentation in the ceiling that we always looked at and remembered. That was the object lesson of playing cribbage for even small amounts of money for points! I’m not sure if he ever paid, but it was a very funny moment.

Gambling was one of the more exciting things we did. The informal rule at the school was no money on the table. So we gambled out of our pockets so that if anyone came in, it would just look like you were playing poker or blackjack without money. But, of course, playing for money was what made it fun. The idea of playing blackjack without playing for money was ludicrous.

I think about these games on a lot of levels. The cards were to a certain extent the same as sports. It was a social thing to do, and there was a definite effort at fairness. We were all trying to have fun together. And so without really being conscious of it, we taught ourselves how to live with each other. We had to make our own rules and they had to be fair or else no one would be in the group, since everyone was in the group voluntarily. How to work with people was really the important thing that was going on educationally. That’s the hardest thing to explain about the school, because it’s not as if you’re trying to teach yourself these skills. You’re doing something for your own fun and then it happens. Suddenly you realize you’re someone who knows how to deal with people.

I didn’t really think about getting an education. I didn’t understand the idea of having to artificially “get” an education. I thought that you lived in the world and you got smarter because every day you were learning. I thought that there was no way to get dumber unless you were erasing stuff out of your brain. It seemed to me that one day you were talking to someone about one subject and another day you were talking to someone about another, and that eventually you’d get around to all of them.

I perceived visitors (and I think a lot of other kids did too) as essentially hostile elements. They were adults who came into the school with a lot of notions from the outside world, so we very quickly formed a picture of how different we were. Visitors would ask you questions which showed that they had no concept of what you were doing. It was as if a Soviet citizen came to America and said, “So, what do you do when the Secret Police knocks on your door?” It’s like, wait a second, I don’t think you’ve got the concept here. They would say “What classes do you do?” And you’d be thinking, “Classes? We don’t do classes, you know. Look around. There are no classrooms here.” And then they’d say, “What did you learn today?” And we’d think, “What did I learn today? What are you talking about?” Because it wasn’t like you went into the library and learned your facts for the day. We weren’t learning subject by subject. We were learning in a much more organic manner. I can compare it to the way you learn about a job when you go to it and you work in it for six months: if your supervisor came up to you every day and said, “What did you learn today?” you probably wouldn’t have that much to tell him; but after six months you suddenly realize you know how to do the job. You would be doing a lot of different things and you would learn them in little bits and pieces that would start adding up to much bigger pictures. By the time you were done learning about something, it was coming from so many different sources, from books and from people you were talking to, and from a long drawn out experience, that you had no idea. When I was six years old, I could describe perfectly how a still worked cause I had hung out with Ken. He didn’t sit down and say, “This is how a still works”. He built a still and we watched him build it, and asked questions, and over the course of a few weeks, we figured out the process of distillation. It wasn’t part of a chemistry class. It was watching some kid do something. And he didn’t stop and give you a rundown. He just did it, and you watched and suddenly you realized you had figured it out.

I was, however, aware throughout my childhood that this was an experiment and that we were definitely there to learn. There was no question about that, because all the hostile adults made it clear that you better learn something or this whole experiment was a flop.

I don’t recall thinking of reading as something you learned. I never saw a kid in a reading class, but one by one my friends would be reading. I’m not sure reading is a significantly different process from learning how to talk. You don’t have talking lessons for babies, and they learn how to talk. When you have a lot of books around and kids reading to other kids all the time, people just learn how to read by osmosis. I remember thinking of learning skills in cooking. You learned how to make an apple pie. But, of course, doing it with Margaret was so much more fun than doing it yourself that you never really learned it. You just had her teach it to you again and again because it was so much fun to do it with her!

With photography, I sat down and very deliberately read a small library’s worth of books about photography and I taught myself how to do darkroom work. I spent a lot of time in school doing photography. I had always thought I wanted to shoot nature documentaries when I grew up. I thought there’d be nothing cooler than trying to take a picture of an ant in its anthill.

I had never built anything in my life. My parents did not even have tools around the house. I went to the guy who ran the woodshop and I said, “I want to make a nice darkroom. I want to tear out this thing here and put counters there and build this rack here.” I had a little design in mind from all the things I had read. He helped me, and those were my only real carpentry lessons. The photolab didn’t have any money, and all that was there was an enlarger in a bathroom, basically, and a bunch of trays on a table. We did the whole thing. We found old wood, we took nails out of it, we put formica on it. It was incredibly cheap: it cost forty dollars. To finance it, I started developing film and doing proof sheets for people around school. A lot of little kids started hanging out in the photolab and learning how to do the darkroom work. From about the age of thirteen until I left school, I was probably in there at least two days a week for all day printing sessions. The more I did it, the more I learned about it. There’s only so much that someone can really teach you about photography or about any art form. The rest, you have to learn yourself. There are very few things I did during that period that are exceptional works of photography, but by doing it all the time I became so comfortable with the medium that, by the time I was seventeen or eighteen, I was starting to do mature work.

I had an apprenticeship set up through the school with a very sweet man who loved the idea of the school, and loved having me as an apprentice. He taught me how to print professionally. I worked for him three days a week. We’d print all day, and everything I worked on came from professional photographers, so I started learning how they shot, and I started meeting them. I also learned how he ran his business. During the year I was with him, he was in a crazy loft he was sharing with a bunch of artists, which was also very influential in my life, because it was the first time I was exposed to a lot of musicians and artists who were living in the real world but without jobs, and they made me realize it was possible. These were guys who just did odd jobs, played gigs, assembled computer boards at home. They lived very cheaply and did their art. That was an amazing revelation to me, because I grew up in the suburbs. I suddenly realized that you could just go from week to week doing a little of this and a little of that and actually be doing your art and what you wanted to do.

The photographer moved and I helped him construct the photolab and watched him design his dream space. By the time I finished working with him, I was an expert black and white printer. He also helped me get my next apprenticeship with a fairly big commercial photographer in Boston. There I learned how to use the large format camera, studio lighting, and all that. I was basically his assistant, but he paid me because I was working well, and I moved out of my house. I’ve been out of the house and living off photography ever since.

I was also playing a lot of music then. I would be at school playing music, and I would be at the studio doing photography. I guess this is a thing that is typical of the school in the totally random way it occurred. Music was coming into my head. I was not seeking it out. I would just be walking along and I’d be humming a tune and I’d start thinking about my life as a teenager and words would be there. It’s an incredibly expressive time in your life. You’re falling in love for the first time. You’re about to become an adult, but you’re not quite one yet. You wish the world was a perfect place and you’re realizing all the ways it’s messed up. Lots of very powerful emotions.

My friend Alan, who played classical piano, happened to say one day, completely casually — so casually that he doesn’t even remember saying it to me, even though it changed my life — “Why don’t you just try picking out some of those tunes on the piano? It’s not that hard to pick them out by ear, and you could probably play along with them a little and it would be better than just humming.” I couldn’t believe how easy it was to pick out a tune on the piano that was already in your head because you knew when it was wrong and you just kept picking away until you found it. Suddenly I was playing four fingered piano, three fingers on the right, one finger on the left. I was writing a lot of songs and playing whenever I had the chance. That kept building as an interest.

I had two siblings in school, separated by many years. I probably was less aware of my sister who was two years younger, than I was of my little brother who was ten years younger. But I didn’t necessarily see them that much. Everyone was extraordinarily mobile. Trying to find a kid at the school is like trying to find a needle in a haystack. They’d be there one minute and gone the next. Mobility was a big part of what was different about the school from any other institution. That’s something that people have a really hard time understanding. Mobility and randomness together let you find the things you’re interested in. You’re not stuck anywhere. The minute you’re bored, you zip somewhere else and find something else you’re interested in, so that the whole day you’re doing stuff you’re excited about. There’s a lot of stuff going on. Other kids are doing things. There are books, and activities, and people for you to bounce your ideas off of, so you’re not just creating the world out of whole cloth yourself. Part of it is stuff you’re creating and part of it is just stuff you’re walking into. Part of the fun of school was spending whole parts of the day walking from room to room, seeing what was going on in each room before finally settling down and deciding to do something in a particular place. If you were bored you’d say, “Hey, let’s go see what so and so’s doing.” And you’d spend half an hour finding so and so and seeing what they were up to. The staff were also a fairly mobile group, but they would tend to confine themselves to the building, and they also tended to be in certain rooms. You wouldn’t be likely to find a staff member in a reading room because a staff member isn’t going to sit down in the middle of their work day and start reading a book. You were not as likely to find a staff member in the smoking room or in the music room.

The end of the day had a whole different feeling from the rest of the day. Around the time the school was closing, there would still be the few diehards, the people who really loved staying until the last minute, or whose parents didn’t pick them up until late. Because there were so few of us, we would tend to gather in the kitchen and talk to each other, or maybe play a game of cards. After 5:00, the lunches of all the people who had checked out were up for grabs, so we would pick through everybody’s lunch to get the good stuff. That was one of the benefits of being last. You might go up to the music room and play music really loudly because you knew it wasn’t going to bug anyone. So there was a whole end of the day world that I was often part of. Then you’d see your siblings because people would tend to cluster together more at that point in the day.

My sister and I had a lot of the same friends. Often, she would be friends with the younger sisters of the kids I was friends with. But my little brother is ten years younger than me. So I’d be keeping an eye out for him, because you never knew what those little five years olds could get into roaming around completely unsupervised! It’s something so hard to imagine that at SVS there are five year olds running around doing whatever they want to. They run off to the sandbox, they run somewhere else and eat — they are amazingly clean considering their age, as far as picking up after themselves. And big kids would play with them all day long. There’s no toy as wonderful as a five year old who’s cute. We’d constantly be reading to them or playing games with them. But every now and then, I’d ask somebody, “Hey, have you seen my brother around? Is he ok?” And they would say, “Oh, yuh, saw him playing down at the pond.” And I’d take a peek out and see this little curly head bouncing around and that would be that.

I probably did not miss a School Meeting between the ages of six and twelve. In my teen years, I very rarely went to a School Meeting unless it specifically concerned me or someone had asked me to come and vote for a motion that they were sponsoring. The School Meeting was a small democratic group, so a certain element of reason hopefully prevailed. But there was also politics. Kids who wanted to have a thing happen would tell all their friends, “Come vote for my motion at the School Meeting.” Sometimes it would backfire on them because they’d get all these kids at the School Meeting and it would turn out they wanted money for private guitar lessons or something and in a very short debate it would become obvious that we couldn’t just give private guitar lessons to every kid who wanted them. They’d be voted down by their own friends they had brought to support them. But that’s politics too. When I was a little kid, I didn’t go specifically to vote on things. I was interested in the older teenagers debating back and forth about what to spend money on or what was the appropriate punishment for a particular type of crime. I don’t think even little kids get swayed by specious argument. I tended to vote as a little kid along pretty reasonable lines. I would just listen to people’s arguments. Now maybe you can say a little kid wouldn’t see the exact subtleties. But it seemed to make sense. And I was as impatient as many of the adults with someone who would be like a gadfly, constantly running the debate around in circles, so when someone finally moved to close the debate, a lot of little kid’s hands shot up too. And not because they were bored. They wanted to get on to the next interesting thing because this debate had worn itself out in their minds as well. Later on, I had more interesting things to do with my time. I felt I could trust whoever was at the School Meeting.

I enjoyed trials. They were like Perry Mason. You could be a juror and that was really fun. In a trial a relatively small and idiotic thing could be turned into a really exciting thing because someone would be maintaining their innocence. Being on the judicial committee was really just a month long glimpse into all the dirty linen of people’s lives. You’d have heart to heart talks with kids, because what are you going to do about a kid who’s always bugging somebody? It’s not like you can throw them out of school. Hopefully after a year of telling these kids to try to be nice, you would make a dent and they would slowly become socialized and realize that the obnoxious behavior patterns that they had been in at home or at another school weren’t working with this group of kids who wanted to relate to them as equals.

The judicial committee was your tool for making people understand that it’s not that running down the hall is the crime of the century; but let’s say I’m walking down the hall with a tray full of fragile things and you run into me — that’s not something I really want to encounter. Learn to live your life in the context of not making your freedom impinge on the freedom of somebody else. I had learned it myself through the same process. I went from being a self-centered person to realizing the effect of my activities in a larger scope, and I would make adjustments to my behavior. There was a period in my life when I got brought up a lot. I was very proud of being tied with some other kid for second most convictions!

The staff members were simply the adults at school. I didn’t really have a division in my mind between adults and kids. They just all kind of melded together. As I got older I realized that the only difference between a staff member and a student was that students were allowed to have fun and staff members had to do certain things that weren’t fun.

As soon as a school job became fun, the staff no longer did it. Chairman of the School Meeting at one point became a fun job for kids to do and every kid wanted to be Chairman. Then the staff were no longer Chairmen. That was it. But they still had to do all the grungy jobs, like Grounds Clerk, which no one else wanted, because it seemed like unrewarding work.

Staff elections were an interesting time of the school year, especially the contract discussions: to see how many days people voted for the individuals and to think about whether these people would want to work for three days instead of five days, and what the actual contract offer would be. There are a limited number of staff days to distribute and when you run out of those days, you run out of your budget, so you have to decide what’s important. The great thing about it was it really did let you weed out. I think that people vote very intelligently. A lot of times people will vote for someone who doesn’t do them any particular good because they have the feeling that person is useful for the school. Little kids vote a little more from the heart. They vote more time for the people who spend time with them but I think that’s an intelligent vote. I think you should vote for the person who you feel is helping you in your education.

Some of the most special moments to me were thesis defenses. The whole school would get together and listen to people’s individual stories. We didn’t have that many graduates in those days. Some of them would do a very straight presentation on what they were going to do with their lives, but a lot of them would do a very touching recap of their life at Sudbury Valley. There were a lot of incredible moments, especially with the kids who had come to us as desperate, really troubled teenagers. Those would be very emotional theses because the person was saying goodbye to all the people who had really turned them around. They were leaving the community, but they were acknowledging how important you were to them and that was always a really beautiful thing.

A lot of people hate their whole childhood, or hate their school, and they really start being themselves when they become adults. I feel like I’m in an accelerated development in many ways; I was able to enjoy a period of my life when most others are waiting for their lives to begin.